Thousand Bagger in Uranium Mining

Stephen B. Roman led Denison Mines from 8.5 cents to $87 per share in 13 years, tussled with prime ministers, and dominated the INSANE 20th century uranium business. This is his story.

Rage filled Stephen Roman’s stout frame as he stormed Canadian prime minister Lester Pearson’s office in 1965. Exploding over a ruined $700 million uranium contract, Roman hurled "son of a bitch" at Pearson, who would later quip that Roman was a relic, lagging "fifty years behind the apes."

It wouldn’t be Roman’s last battle with a prime minister. His improbable rise from tomato picker to mining king is a tale of grit and the dramatic turns in 20th century uranium mining. Pope John Paul II even blessed Roman’s sprawling Toronto estate. Merging business, politics, and the biggest uranium mine, this is how Stephen Roman built an empire.

$30 Billion Uranium Strike

In the cold wilderness of 1953 Northern Ontario, a 90 mile uranium trend was discovered near Elliot Lake. In secrecy, over 100 men staked claims to the area in what became known as the “Back Door Staking Bee”. They worked on behalf of mining legends Joe Hirshhorn and Frank Joubin. The area became America’s major Cold War uranium source. The first of 12 mines opened just 2 years later. By the 1980s, an estimated $30 billion was contributed to Canada’s economy as a result of these finds.

Sensing something was happening, three prospectors led by Art Stollery interrupted the six week Staking Bee. They plied a pilot with whiskey, heard whispers of Quirke Lake action. By dawn, they hit the bush, bumping into Hirshhorn’s squad. Stollery bluffed: "We've staked this already." Confused, Hirshhorn’s crew retreated. Stollery snagged 83 claims in 48 hours. Just a sliver of a 90-mile, 1500 claim expanse. But fate smiled. Little did they know, they stood atop the world's richest uranium deposit.

But Nobody believed Stollery’s claims had value. Hirshhorn himself refused to buy them, feeling cheated. In early 1954, Stephen Boleslav Roman, a forceful young Slovak immigrant to Toronto seized the opportunity.

Roman bought Stollery’s claims personally on a promise of $30,000 cash and 500,000 shares of his penny stock shell, Denison Mines. Roman had recently bought 900,000 shares of Denison for 8.5 cents a piece and become its president.

With Denison stock swinging between 30 and 60 cents ahead of drilling, a $30,000 drill program found a rich uranium deposit by October 1954. It eventually contained 367 million pounds grading 0.14% uranium. Annual production would equal all of America’s mines combined.

Joe Hirshhorn was the man every young mining entrepreneur aspired to be in Canada (Read all about Joe in last week’s profile). He lived large, enjoyed immense success, and had the greatest access to capital. The upstart Roman once pleaded for a meeting with him in 1946, when Hirshhorn dismissed him, saying, “Don’t waste my time.” In the great Elliot Lake uranium strike, they would become bitter rivals.

“You’re a horse’s ass,” Hirshhorn told Roman in one showdown. “I’m a farmer, and that’s a compliment,” Roman responded.

Hirshhorn would cash out of the Back Door Staking Bee early and build America’s largest private art collection. Roman controlled his mine til his dying day.

In a rush to secure uranium for bombs and power plants, the US Atomic Energy Commission pledged to buy Denison’s output at cost plus profit margins “in the order of 200%... A sweeter deal couldn’t be imagined,” author Paul McKay wrote in The Roman Empire (1990). A $202 million 5 year contract was signed, construction loans were facilitated, and the race to build a mine was on.

Just three years after discovery, a $37 million mine came on stream in the remote wilderness of Northern Ontario. First uranium shipped in June 1957.

By 1962, Denison had retired its debt, earned profits of $61 million, and paid dividends of $18 million (37% to Roman). Only a fraction of its deposit was mined, and Denison sold at $10 per pound with production costs of only $4. Uranium had surpassed gold and copper as Canada’s largest mining export.

$1,000 invested in Denison in 1954 grew to $37,000 by 1962, when Denison traded at $12 per share. Those same investors earned dividends of $15,000 along the way, according to McKay. Denison diversified into oil, cement, phosphate, baking, banking and other industries.

But 10,000-plus nuclear warheads later, the US was awash in uranium and stopped buying. Panic spread in Elliot Lake. All but a few of the 12 mines kept operating, including Denisons. Of 9,000 mining jobs in 1959, just 1060 remained in 1964.

Needy for new buyers, Denison sold 5.6 million pounds to Britain in ‘62 at $4.38 per pound, less than half of USAEC prices. Roman also convinced the Canadian government to stockpile $25 million worth at $4.32 per pound between ‘63-’65.

The Fast Talking Frenchman

In the early ‘60s, a suave, fast-talking Frenchman, Jean Bodson, arrived on Denison’s doorstep. He promised access to lucrative French contracts and Roman took a chance on him. But there was a catch. Denison needed to grease some wheels. It bought a random gravel pit near Paris, a finance company for Bodson, and opened a lavish office for him. Bodson was also promised a 3% success fee.

Finally, in ‘65, Denison landed a 100 million pound, $700 million French purchase order. Pressured by US president Lyndon Johnson to deter France’s entry to the nuclear club, the Canadian government blocked the deal. This led to Roman’s fiery showdown with Pearson. Making matters worse, Bodson sued Denison and won an additional $5 million fee because the contract had been signed.

After making a multi-million dollar cash withdrawal from Denison’s account, Roman flew the company jet to the Bahamas for a face-to-face meeting with Bodson. “How much money he gave the Frenchman is still a secret... [Roman] brought back no receipts,” McKay wrote.

To placate Denison and support Elliot Lakes miners, Canada agreed to stockpile another 15 million pounds at $4.90 from ‘64-’70. Denison was still earning a profit with costs of $3.10. New orders started trickling in from Japan, including a $300 million commitment starting in ‘74.

Then in 1970, Continental Oil bid $104 million for Roman’s 36% Denison stake, a massive sum in those days. New prime minister Pierre Trudeau opposed control of Denison leaving, and Canada blocked that deal as well. A furious Roman went back to the Prime Minister’s office in a “verbally bloody encounter” that was unable to persuade Trudeau. Roman then sued Canada and lost. He appealed and lost again. But Canada agreed to stockpile another 6.4 million pounds at $6 per until ‘75.

Canada-Led Cartel Leads to 700% Price Hike

Barred from US exports, the Canadian uranium business was fighting for survival in the early 70s. The federal government, awash in stockpiles, hatched a top secret plan: form a cartel with the major producers. A new floor price was set ($6.25 for Europe, $6.55 for Asia, because, Asia…). Cartel members would take turns winning contract bids.

The cartel had a major impact on the uranium market. Customers began outbidding each other, generating windfall profits for miners. This was a lifeline for Denison, threatened by new richer discoveries in Saskatchewan and abroad.

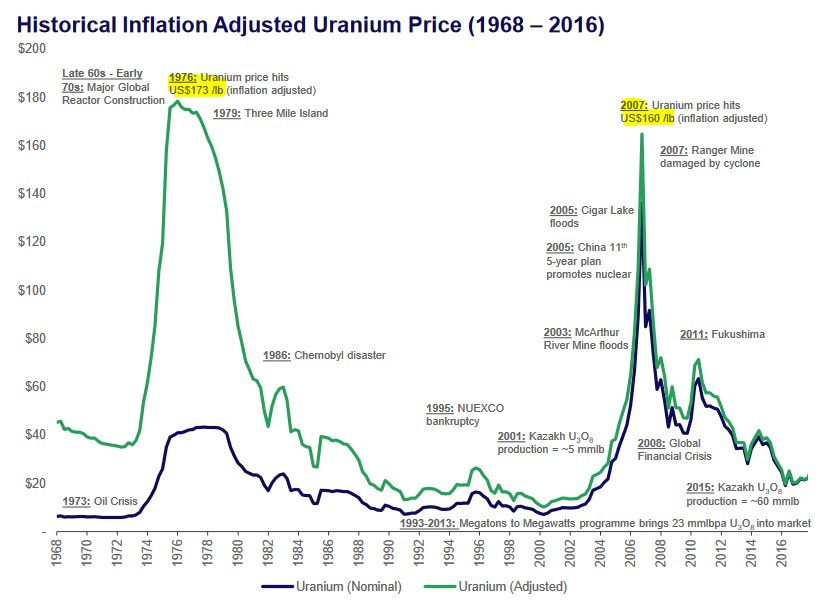

In 1975, reactor builder Westinghouse fell into the cartel’s trap. They’d promised customers uranium at $8 per pound, but the new world price had moved to $26. Facing $2 billion losses, Westinghouse defaulted on its contracts. Panic ensued and uranium prices ripped to $42. It was a 700% price climb in just 5 years.

Then news of the cartel leaked. Trudeau barred any Canadian from speaking of it under threat of 5 years in prison. Roman denied the cartel’s existence.

In ‘81, Denison and others were charged criminally. Two years later, Canada’s Supreme Court ruled that companies acting under the direction of the government could not be charged with crimes, dropping the case. However, Denison still settled with Westinghouse for an undisclosed sum.

Mega-Deal Costs Ontario Taxpayers Billions

Utility provider Ontario Hydro had an ambitious plan to build nuclear reactors in the ‘70s. They needed uranium, and as cartel-rigged prices rose, they became concerned enough to consider buying Denison.

Roman played hardball. After years of fierce negotiations, Ontario Hydro agreed to buy 126 million pounds from Denison over 30 years at escalating prices. The deal was worth $4.7 billion to Denison, with a minimum profit of $630 million.

The Ontario Legislature voted down the deal, but the premier signed the contracts into law in Feb ‘78 as uranium prices peaked. It was an incredible deal for Denison and cost Ontario taxpayers billions. In 1990, Ontario Hydro was buying uranium from Denison at $70 per pound, while the world price was under $10. Ontario Hydro had not pursued its aggressive nuclear plans after all.

The Roman Empire

With Denison stock trading above $70 for the first time since the ‘60s (it reached $87 per share in ‘67, a ~1025X leap from 8.5 cents in ‘54), Roman and Denison were on top of the world again.

"In a neat blue suit, his face always somewhere between a glare and a grin, Roman lives up to expectations," Macleans magazine’s Angele Ferrante wrote in a 1978 profile. "His faith floods the room."

Roman was chauffeured to his opulent, oak-panelled offices in downtown Toronto in a Fleetwood Cadillac. Behind his massive desk, he peered down at visitors from a chair on a hidden, raised platform atop plush, red carpets. Richard Nixon joined him for lunches prepared by Denison’s private chef. At his 1200 acre “Romandale Farm” 30 minutes from Downtown Toronto, Roman lived in a 17 room mansion with wall to wall marble and gold-plated fixtures. He owned a crystal chandelier that once belonged to an Indian Maharaja. Roman said it took a dozen maids three weeks to clean the chandelier each year. He bred the finest Holstein cattle in 8 barns at Romandale (he once paid a record $1.45 million for a pure-bred). In 1984, Pope John Paul II personally visited and blessed the $25 million cathedral Roman was building there.

“I don’t like your word opulent,” Roman once told a reporter. “Christ is the complete ideal. Don’t forget that he wined with people, and was called a glutton by the Pharisees. I think Christ liked nice things. The Bible doesn’t say that a man can’t be wealthy.”

"His bottom line is faith,” continued Ferrante. “He just believes-in himself, Denison Mines, Roman Catholicism, capitalism and the emancipation of Slovakia, the country of his birth. "Everybody is put on this earth to perfect a divine plan,” he says. "Mine is to save my soul."

Genesis of Steven Roman

Roman left Slovakia in 1937 when he was 16. He studied agriculture and picked tomatoes initially, then joined a World War II munitions plant as a factory worker. Ambitious for greater things, Roman played the penny stock market.

According to Paul McKay, Roman and a colleague tracked down Viola MacMillan, Canada’s mining queen, in a remote cabin near Timmins, Ontario. They “slept on her floor, and primed her for every detail on how to find, stake, and promote mining claims.”

Roman founded Concord Mining Syndicate in 1946 with ten partners pooling $2,000 each. When a mining company bid $500,000 for one of their staked projects (a $50,000 payday per partner) after a nearby gold strike, Roman agonized. He’d sold the claims days earlier for $150,000.

The young Roman scoured Canada, staking prospects near exciting discoveries. This included oil production in Saskatchewan as Alberta’s great Leduc oil strike was underway. “Roman, shrewdly, was into the right thing – not quite in the right province but clearly at the right time. This is close to the perfect formula for success in financing speculative ventures,” Frank Joubin wrote in his autobiography. The Northern Miner estimated Roman earned $2 million from these oil ventures by 1953, the year before his uranium strike.

The brash Roman was never quite accepted into the WASP-dominated Canadian business establishment, where a big bank directorship was typically offered to a man of his stature. "If Roman was a Scot, his stock would be selling for much more,” a Toronto portfolio manager told Ferrante in ‘78. “It's as simple as that. Hunkies are not supposed to make that much money."

In the ‘80s, Denison made a huge ill-fated bet on a BC coal project that hurt the company. When Roman died in his sleep in 1988 at 66, his daughter Helen took over Denison, soon facing numerous challenges. Ontario Hydro finally got out of their uranium contract. The Elliot Lake mine was decommissioned in ‘94. When Helen resigned from Denison in ‘99, Roman’s shareholding had been diluted from 36% to 3.5% amid restructurings to avoid bankruptcy. The stock had fallen all the way down to 11 cents.

Stephen B. Roman’s legacy is tangled. An avowed free-market capitalist, he cozied up to government when it suited him, such as in the cartel saga. Critiques, especially from McKay, paint him as negligent, particularly for skimping on early vital mine ventilation, putting miners at risk.

Roman was survived by his wife of 43 years, Betty Gardon, who died in 2017. The Romans had 7 children. Stephen Roman Jr. today leads Niger uranium developer, Global Atomic (TSX:GLO - $654M market cap). 35 years after Roman’s death, a restructured Denison (TSX:DML - $2.1B market cap) is still active in the uranium business today.

“Stephen Roman was a brilliant competitor whom I greatly respect,” Joubin told the Northern Miner. “His qualities of global imagination, self-confidence, financial courage and sound judgement were extraordinary. He had few equals and no superiors in the intensely competitive world of mine finders.”

“[Elliot Lake] was the cork in a bottle for Steve,” said Joubin. “He opened the bottle and the genie emerged.”

Sources

The Roman Empire by Paul McKay (1990) https://a.co/d/76BvCKA

Not For Gold Alone: Memoirs of a Prospector by Frank Joubin (1986) https://www.amazon.ca/Not-Gold-Alone-Memoirs-Prospector/dp/0969379307

Macleans magazine archives (Sep 26, 1959, Jun 26, 1978) https://archive.macleans.ca/library

Stephen Roman dead at age 66: The Northern Miner (1988) https://www.northernminer.com/news/stephen-roman-dead-at-age-66/1000121179/