Ross Beaty's 80 Bagger in Copper Mining

The Lumina Copper Story

“Comfortable with ambiguity,” reads the sign on Pan American Silver chairman Ross Beaty’s office door. It’s a fitting mantra for the mining magnate and environmentalist: over the course of his career, he’s made billions in non renewable resources, but now devotes much of his time advocating for sustainability. “If there’s anything I can do to change the direction of global consumption, I figure I should do it as a service to my kids and the world at large,” Beaty told us in an hour-long interview on Tuesday.

“Nature has a way of asserting herself, but I don’t think we should wait until it’s too late. Reducing our ecological footprint doesn’t have to reduce our quality of life — we have the knowledge to make the change. I’m just trying to help catalyze it.”

Through his nonprofit, the Sitka Foundation, Beaty backs environmentally conscious organizations. He also invests a large portion of his personal capital in green business and renewable energy.

But Beaty’s better known as a mining industry entrepreneur. Most notably, he founded Pan American Silver — one of the world’s largest primary silver producers — and the Lumina Copper franchise, an enormously profitable venture that earned Beaty the nickname “the broken slot machine.”

Lumina — pulled out of thin air

“Lumina was an epiphany,” Ross told me, describing the endeavor. “In December 2001 and January 2002, the low metal prices were killing Pan American Silver. We were literally month to month.”

Beaty began trying to figure out how he could capitalize on the market misery. After reading an article on long-term commodity price trends (“Fifty-Year Trends in Minerals Discovery — Commodity and Ore-Type Targets,” by Chris Blain, 2000) that argued we were using resources at a higher rate than we were finding them (and therefore approaching a supply scarcity and higher prices), Beaty had an idea that would soon become the stuff of mining legend.

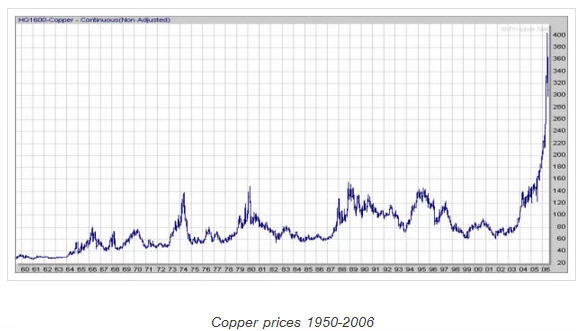

“The article covered gold, silver, copper, nickel, all kinds of metals,” he told me. “And the most classic one was copper. Blain showed the price of copper for the last 50 years had gone through four or five big swings. The cycles averaged eight years long, and it was a sine wave, with increasing amplitude over time.”

“A 10-year-old could have looked at that curve and connected the dots,” he said. “We weren’t just at the bottom of the curve — we were below the bottom. It had to go up. It had done so for 50 years!”

Wanting to take advantage of a bear market where prices would likely rise, Beaty put two and two together. “I decided to go long copper and build a copper option play, much like we built a silver option play with Pan American. We focused on copper development and exploration assets with no geological risk. Just price risk. So we went on a shopping spree in 2002 and early 2003, buying deposits that were uneconomic at the time.”

“We stopped buying assets in autumn 2003, when the price of copper went up. But we had paid almost nothing, and ended up with ten deposits — all big, known deposits — and took it public at a buck a share and gave our original investors warrants. The guys on that IPO made about 80 times their money, so it was a good return. We cashed out and sold five companies. We have one left, but we mostly got our timing right with our exits. We exited four of the companies before the crash, and our royalty company in 2011. What remains of Lumina Copper, the Taca Taca project, is the best deposit in the worst market.”

King Canute

I wanted to give Ross a chance to promote his current portfolio, which includes Pan American Silver, Lumina Copper, Alterra Power, Anfield Nickel, and others.

“You can pound the table all you want, but if market sentiment for your sector is poor, it’s like being King Canute sitting at the edge of the shore, commanding the tide to come in, when, in fact, it’s going out,” he said.

Beaty’s realistic about his ventures. And although Alterra Power — his diversified renewable energy company — has had a “dreadful” market performance, Ross is “working hard to build it into a bigger and stronger company.” He even made a huge investment in it last week.

“The only way I can prove to people that I believe in this company is by buying the stock myself,” he said. “I’d buy the whole company if I could. And maybe I will.”

The conversation shifted to Lumina Copper, in which Beaty has confidence in the project, but not its jurisdiction. “Taca Taca is the best of all the copper deposits we’ve ever worked on. But it’s sitting in a country that’s gone very protectionist, and it’s considered a pariah amongst mining companies who want to build big mines,” he said. “Argentina has unfriendly foreign investor policies today, but that won’t last, and the country has many excellent attributes too. Our objective is to transfer the asset to a major company who can spend $3 billion and build a new mine.”

Ross didn’t speculate about when that would happen. “We had a great offer a year ago, just when Argentina was going goofy, and it disappeared.”

But he’s happy with what analysts are saying: that Pan American should be worth $28, despite the fact that it’s bumping around at $12.50, and that Alterra should be at $.90, despite it actually being at $.33.

“Nobody believes the analysts these days. They’re suffering a credibility problem. Our entire sector is suffering. But that will change,” he said.

With the success Ross has had, he doesn’t need to promote as much as others — when he moves, the market pays attention.

On growth and commodities

“I see real challenges with businesses that require economic growth as a core factor in their success, and unfortunately, mining is in that category to some degree at least,” Beaty told me. “The supercycle is about prices being higher for longer, and I think that’s intact, but I don’t see prices doubling from today’s levels.”

Rather, Ross thinks metals prices will stay static across the board. It’s the reality of the world now, he told me. “Growth isn’t happening because the world’s developed nations simply can’t support it, given existing energy, consumption and population trends. Governments are trying to juice the system with more and more debt and it’s just not working. They would be far better off trying to live within more realistic growth assumptions – not relying on the myth of limitlessness.”

“Commodities sometimes behave like wild animals: they could fall much farther, overnight,” he said. “I don’t know if we’re at the bottom. I don’t think it’s time for me to invest just yet, but its getting close.”

Gold is the exception

Ross expects commodities to be flat, but not gold (and its cousin silver). “Gold is currency. As we print more money, gold will look better and better,” he said.

“Gold will always be attractive to investors worried about governments stealing or debasing their money. Despite the price quintupling over the past decade, gold supply has barely increased at all. When the price of anything goes up by five times, supply always goes up — but not gold. It’s 100% geology.”

On wealth creation through junior resources

“A great discovery will always command value. I don’t think the minerals sector will ever look like the pre-2008 market when it was being turbocharged by the easy-money bubble and by one-off growth in China and other developing nations, but it’s non-renewable, so the business of large mining companies buying small ones will always exist. It’ll just be at a lower level than it has been for the last ten years.”

Given the heavy costs and drain of management focus that come with investor relations, l asked Ross whether mineral exploration should be privately financed, rather than public. “It can’t be private,” he said. “There isn’t enough private money willing to take bets on high-risk projects. You need a public, liquid market, because many investors can only buy companies where there’s liquidity.”

“Even an idiot can make a great discovery and drive a stock from three cents to three bucks, and those guys wouldn’t get funded privately. It has to be public,” he said.

His advice for junior resource companies: “Put your head down, work hard, extend your capital as far as you can. If you can do a joint venture on a project, do it.”

“Don’t ignore IR,” he added. “You have to communicate what you’re doing, but don’t push a lot of money at it. Spend your time and money on a basic IR program talking to shareholders, but don’t blow your brains out on advertisements and conferences.”

Just dues

When I asked him about his peers in the industry, Beaty showered Lukas Lundin with praise. Rick Rule’s another one of his favorites — “the smartest investor in the business.”

Ross also has been buying Pretivm Resources, and likes what Mark O’Dea is doing with Pilot Gold.

But, in general, Ross isn’t investing too much. “We’re looking at things, kicking tires — but we still haven’t found the right stuff.”

“Success takes all types,” Beaty continued. “I’m not terribly good with people — with communication — but I’ve been very lucky, worked hard, had great colleagues, and I’m a decent salesman. Good salesmanship is important. You can’t learn it, it’s just in you. Thank God more people aren’t good salesman, otherwise our society would implode,” he laughed.

When I challenged Ross about his convictions, asking him what one man could really do about the environment, he just smiled and told me, “You say impossible, I say possible.” Confidence and optimism pretty much sums him up.