Escrowed Securities

Cheap stock you can sell expensive for a big profit

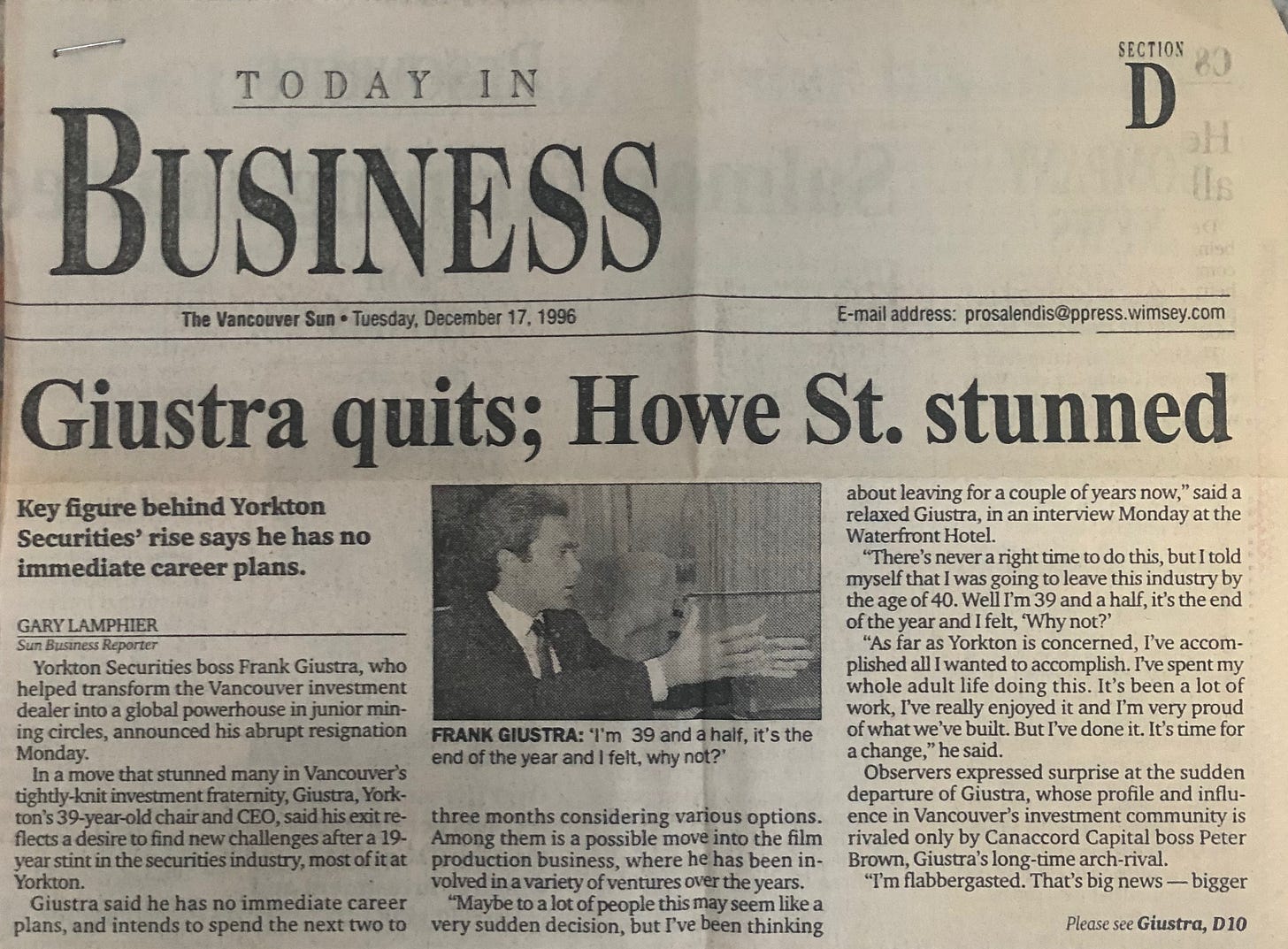

The mining world was stunned in December 1996 when 39 year old finance wunderkind Frank Giustra retired from Yorkton Securities, the investment firm he helped build to prominence in the late 1980s and 1990s.

Giustra’s departure from Yorkton came just weeks before the $6 billion gold exploration fraud at Bre-X unravelled and brought the gold sector to its knees (Giustra was not involved in Bre-X). In the five year mining bear-market that followed, Giustra created Lionsgate Entertainment, the now celebrated hollywood studio. He returned to gold in 2001, re-launching with Ian Telfer, Wheaton River Minerals, which became Goldcorp and reached a peak market cap of $50 billion.

There is a little known aspect to this story, aside from Giustra’s remarkable timing. He has a knack for being lucky, and putting himself in a position to be lucky.

While at Yorkton, Giustra’s top banking client was then up-and-coming mining mogul Robert Friedland. Giustra helped Friedland create and finance such high-flying exploration ventures as Vengold, Fairbanks Gold, and Diamond Fields International.

Diamond Fields was organized in 1993 to prospect for diamonds offshore Africa, and Giustra helped arrange an early fifteen cents per share Presidents List financing for the company. When Giustra presented the list to Friedland which included Giustra and many of his friends, Friedland demanded Giustra prevent the cheap-stock holders from selling early. A multi-year escrow schedule was agreed to and only Friedland could approve an early release.

In one of the most sensational stories ever in mining investment, Diamond Fields lucked into a giant nickel find in Eastern Canada, and shares in the company soared to nearly $200. Ultimately Inco acquired Diamond Fields for $4.3 billion in 1996, just a few months before Giustra’s early retirement.

Giustra says he would have sold too early if not for the lock-up. The forced escrow led his return into 1000x territory, and helped make him a wealthy man.

---

Why Escrowed Securities

The thrill of a venture investor is when you own an in-the-money security that is not yet free-trading. You never know if you will be able to cash-in until the hold comes off.

Venture-stage companies that are raising money often restrict the re-sale of those securities, in hopes their investors will be more patient to let the business develop prior to selling out.

The thought is, if the investor sells too early and too much, the excess supply may harm the share price (share price reflects supply and demand of shares) and could make it difficult for the issuer to finance again.

Additionally, public market purchasers may be at a disadvantage over private buyers that the exchange itself escrows certain securities, such as those sold cheaply or issued to acquire projects.

From time to time, I have made early-stage investments in various private and public companies with varying escrow terms.

The first time I held stock that was considerably in the money, I hardly slept the night before the hold came off. I was so excited to sell in the first few minutes of trading that I knocked the price down and left money on the table as the price quickly recovered.

I once experienced a life changing return as a result of an escrow situation. In 2015, a long-term friend, Brian Paes Braga, invited me to acquire a small stake in the private company he was using to acquire lithium exploration ground in Nevada. That private company was subsequently acquired by a dormant TSXV shell, Royce Resources, and the merged entity became Lithium X Energy.

We seeded the private company at $0.01 per share in 2015. Knowing we had paid so little, the exchange restricted the selling of our cheap-stock on a schedule: 10% would be free-trading initially and 15% every six months thereafter. Fortunately, the escrow kept me in the stock and allowed me to realize a 25000% gain in under 3 years. In 2018, Lithium X was acquired by a private equity investor for $265 million or $2.61 cash per share and my lean years ended. Finally.

Most ventures fail and Lithium X was the exception. Just as easily as an escrow can prevent a holder from selling early and missing out on a great run, an escrow can prevent a shareholder from selling when there actually is an ability to.

What is Cheap Stock and How to Get it

Cheap stock is stock you can sell expensive for a big profit. To me, cheap stock comes from a promising venture that has a valuation of under $5 million and ideally under $1 million so that if it succeeds in building a big business you own a big enough piece. It is developing a new, big idea and fostered by great people.

Here are five ways to get “cheap stock” in Canadian listed venture companies:

Buy shares in the open market, assuming few other market participants are interested in it. If the market knows something is great, it prices it accordingly.

For vending in a property, project or private business into a listed company in exchange for shares or finders fees.

Buy cheap stock in a private placement financing by the company. When a promising company is in its earliest stages, you may know someone involved and gain an opportunity to invest at the founders price of pennies per share. Private placements are often priced at a discount to market and include sweeteners such as warrants so that the purchaser may buy more shares at low prices in the event of success. Private placements are typically subject to a four month hold. You need to meet one of several Accredited Investor exemptions to be eligible to participate.

Buy publicly traded cheap-stock from existing holders in a private transaction. A lawyer and his friends may end up owning a large percentage of an inactive publicly traded company, and then sell their shares to a new ownership group who develops that shell into a new business at hopefully, higher prices.

By working at a promising issuer you may gain cheap stock in the form of equity compensation, stock options, RSUs, etc. Sweat equity.

---

Last week, I wrote about Boris Wertz’ good name in venture capital, and shared a quote of his, “An investor should be your biggest cheerleader and most trusted partner.”

The quote made me wonder why private venture investors are so friendly while public venture investors seem much more hostile.

Last summer, I was catching up with a former colleague over lunch and he started telling me about a new venture he was involved in. I agreed to give him a small investment and he let me know the securities would be escrowed for a year.

My colleague has done well with his company, signing promising joint ventures and attracting investment at higher prices. The stock I bought is up more than 300% on paper. The escrow is due to come off the first half of my share position next month, which I am pleased about, but not counting yet.

Last week he called me with a tough-ask. Would I be willing to extend the voluntary escrow another 3-6 months to give him more time to build the company?

I am torn over it. On the one hand it is just a few months, and the goal is a good one. On the other hand, winners are rare. There is a reasonable chance liquidity could dry up in the meantime, and I may not be able to recoup my original investment if that happens.

This was my response:

“I prefer to not participate in extending the voluntary escrow, and keep the original terms. It is relatively small size. I took a risk and do not want to make things harder on myself. I do not want to disrupt your market either, nor ruin our relationship, and believe I can make us both happy. Do u trust me?”

Long story short, I have alienated my former colleague and I don’t feel great about it. My position is small and I never planned to blow the stock out anyway, but rather to sell a few thousand shares a day until I had recovered my cost-base, after taxes. And I haven’t even sold a share yet but now it looks like I am an antagonistic Howe-St investor. Shit.

Investors, would you sign it if you were me?

Issuers, am I missing something?